Battle of Kosovo

- This page is about the Battle of Kosovo of 1389. For other battles, see Battle of Kosovo (disambiguation); for the 1989 film depicting the battle, see Battle of Kosovo (film)

| Battle of Kosovo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ottoman wars in Europe | |||||||

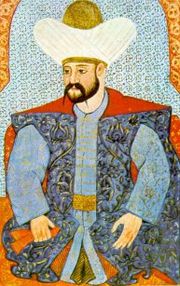

Battle of Kosovo 1389, sixteenth-century Russian miniature |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Murad I † Bayezid I Yakub † |

Lazar Hrebeljanovic † Vuk Brankovic Vlatko Vukovic |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~ 27,000-40,000[4][5][6] | ~ 12,000-30,000[4][5][6][7] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Heavy casualties. Sultan Murad I assassinated by Miloš Obilić. | Most of the Serbian nobility including Prince Lazar Hrebeljanovic were killed during the battle. | ||||||

|

|||||

The Battle of Kosovo (Serbian: Kosovska bitka, Turkish: Kosova Muharebesi) was a battle fought in 1389 on St Vitus' Day, June 15,[8] between the Serbian principality and the invading army of the Ottoman Empire under the leadership of Sultan Murad I.[9][10] The battle took place in the Kosovo Field, about 5 kilometers northwest of modern-day Pristina. Reliable historical accounts of the battle are scarce; however, a critical comparison with historically contemporaneous battles (such as the Battle of Angora or Nikopolis) enables reliable reconstruction.[11] The battle was an Ottoman victory, with heavy losses on both sides.

The Battle of Kosovo is particularly important to Serbian concepts of history, tradition, and national identity.[12]

Contents |

Preparations

Army movement

After the defeat of the Ottomans at the Battle of Bileća and the Battle of Pločnik, Murad I, the reigning Ottoman sultan, moved his troops from Philippoupolis (Plovdiv, in present-day Bulgaria) in the spring of 1389 to Ihtiman. From there, the party traveled across Velbužd (Kyustendil) and Kratovo (present-day Macedonia). Though longer than the alternate route through Sofia and the Nišava Valley, this route led the Ottoman party to Kosovo, one of the most important crossroads in the Balkans. From Kosovo, Murad's party could attack the lands of either Lazar of Serbia or Vuk Branković. Having stayed in Kratovo for a time, Murad and his troops marched through Kumanovo, Preševo and Gnjilane to Pristina, where he arrived on June 14.[11]

While there is less information about Lazar's preparations, he gathered his troops near Niš, on the right bank of Južna Morava. His party likely remained there until he learned that Murad had moved to Velbužd, whereupon he moved across Prokuplje to Kosovo. This was the best place Lazar could choose as a battlefield, as it gave him control of all the routes that Murad could take.[11]

Army composition

Murad's army numbered from 27,000 to 40,000 fighters.[4][5][6][11] Amongst the 40,000 included 2,000 to 5,000 Janissaries,[13] 2,500 of Murad's cavalry guard, 6,000 sipahis, 20,000 azaps and akincis and 8,000 of his vassals from Germiyan, Saruhan, Byzatnine empire, Bulgaria, southern Serbian principalities in Macedonia ( the lands of Constantine Dragaš and king Marko ) and Albania.[11]

Lazar's army numbered from 12,000 to 33,000.[4][5][6][7] Out of approximately 30,000 fighters present, 12,000 to 15,000 were under Lazar's command, with 5,000 to 10,000 under Vuk Branković, a Serbian nobleman from Kosovo, and just as many under Bosnian noble Vlatko Vuković.[7] Mixed with Vuković's army was a contingent of Knights Hospitallers, whom the Croatian knight John of Palisna had led from Vrana in Croatia.[14] Several thousand were cavalry.[15] A number of Polish and Hungarian knights also helped the Christian allies.[16]

The battle

Troop disposition

The armies met at Kosovo Field. Murad headed the Ottoman army, with his son Bayezid on his right and his son Yakub on his left. Around 1,000 archers were in the front line in the wings, backed up by azap and akinci; in the front center were janissaries, behind whom was Murad, surrounded by his cavalry guard; finally, the supply train at the rear was guarded by a small number of troops.[15]

The Serbian army had Prince Lazar at its center, Vuk on the right and Vlatko on the left. At the front of the Serbian army were the heavy cavalry and archer cavalry on the flanks, with the infantry to the rear. While parallel, the dispositions of the armies were not symmetrical, as the Serbian center had a broader front than the Ottoman center.[15]

When a torrent of arrows landed on Serbian armsmen,

who until then stood motionless like mountains of iron,

they rode forward, rolling and thundering like the sea

Start

Serbian and Turkish accounts of the battle differ, making it difficult to reconstruct the course of events. It is believed that the battle commenced with Ottoman archers shooting at Serbian cavalry, who then made for the attack. After positioning in a V-shaped formation, the Serbian cavalry managed to break through the Ottoman left wing, but were not as successful against the center and the right wing.[15]

Turkish counterattack

The Serbs had the initial advantage after their first charge, which significantly damaged the Turkish wing commanded by Yakub Celebi.[1] When the knights' charge was finished, light Ottoman cavalry and light infantry counter-attacked and the Serbian heavy armour became a disadvantage. In the center, Serbian fighters managed to push back Ottoman forces, except for Bayezid's wing, which barely held off the forces commanded by Vlatko Vuković. Vuković thus inflicted disproportionately heavy losses on the Turks. The Ottomans, in a ferocious counter-attack led by Bayezid, pushed the Serbian forces back and then prevailed later in the day, routing the Serbian infantry. Both flanks still held, with Vuković's drifting toward the center to compensate for the heavy loses inflicted on the Serbian infantry.

It is said that Branković had long been jealous of his sovereign. Some historians state that he had arranged with Murad to betray his master, on the promise that he would rule Serbia under the sultan's overlordship. At a critical moment in the battle, Branković turned his horse and fled from the field, followed by his troops. However, historic facts say that Vuk Branković had seen that there was no hope for victory, and fled to save as many men as he could. He fled after Lazar was captured, but in songs, it is said that he betrayed Lazar, and left him to death in middle of battle rather than after Lazar was captured and the center massacred.

Bayezid gained his nickname "the thunderbolt" here, after leading the decisive counter-attack. Sometime after Branković's retreat from the battle, the remaining Bosnian and Serb forces yielded the field, believing that a victory was no longer possible.

Murad's death

Based on Turkish historical records, it is believed that Murad was killed by the Serbian knight Miloš Obilić on June 29, 1389, while Murad walked on the battlefield the day after the fighting had ended. Murad was the only Ottoman sultan who died in battle.

Bulgarian, Greek and Serbian sources allege that Obilić killed Murad during the battle, when Obilić went into the Ottoman camp and entered the sultan's tent in an apparent desertion. Once there he stabbed Murad in the neck and heart. Obilić was killed by the Sultan's bodyguards immediately, or afterward while fleeing on horseback.[17]

The earliest preserved record, a letter from the Florentine senate to King Tvrtko I of Bosnia dated 20 October 1389, says that Murad was killed during the battle. The killer is not named, but it was one of 12 Serbian noblemen who managed to break through the Ottoman lines:

"Fortunate, most fortunate are those hands of the twelve loyal lords who, having opened their way with the sword and having penetrated the enemy lines and the circle of chained camels, heroically reached the tent of Murat himself. Fortunate above all is that one who so forcefully killed such a strong vojvoda by stabbing him with a sword in the throat and belly. And blessed are all those who gave their lives and blood through the glorious manner of martyrdom as victims of the dead leader over his ugly corpse."[18]

Murad's son Bayezid, was informed of the sultan's death before his older brother Yakub. Bayezid sent Yakub a message, stating that their father had some new orders for them. When Yakub arrived, he was strangled to death, leaving Bayezid as the sole heir to the throne.

Aftermath

"Whoever is a Serb and of Serb birth,

And of Serb blood and heritage,

And comes not to the Battle of Kosovo,

May he never have the progeny his heart desires,

Neither son nor daughter!

May nothing grow that his hand sows,

Neither dark wine nor white wheat!

And let him be cursed from all ages to all ages!"

The dying Pavle Orlović is given water by a maiden who seeks her fiancée, he tells her that her love, Milan, and his two blood-brothers Miloš and Ivan are dead.

The battle of Kosovo was a victory for the Ottomans.[19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26] While both armies being virtually destroyed and both sides lost their leaders, the Ottomans were able to easily field another army of equal or greater size, whereas Serbia could not. Because of these losses, Serbia was reduced to a vassal state with Serbian nobles paying tribute and supplying soldiers to the Ottomans.[2] The battle did, however, stop the Ottoman advance into Europe and slowed down their invasion of Serbia. Furthermore, in response to Turkish pressure,[27] some Serbian noblemen wed their daughters, including the daughter of Prince Lazar, to Bayezid.[28][29] In the wake of these marriages, Stefan Lazarević became a loyal ally of Bayezid, going on to contribute significant forces to many of Bayezid's future military engagements, including the Battle of Nicopolis which marked the last large-scale Crusade in the Middle Ages. Eventually, the Serbian Despotate would, on numerous occasions, attempt to defeat the Ottomans in conjunction with the Hungarians until its final defeat in 1459 and again in 1540.

The Battle of Kosovo came to be seen as a symbol of Serbian patriotism and desire for independence in the 19th century rise of nationalism under Ottoman rule, and its significance for Serbian nationalism returned to prominence during the breakup of Yugoslavia and the Kosovo War when Slobodan Milošević invoked it during an important speech.[30]

References

- ↑ Dupuy, Trevor, The Harper's Encyclopedia of Military History, (HarperCollins Publishers, 1993),422.

- ↑ Laffin, John, Brassey's Dictionary of Battles,(Brassey's Ltd:London,1995),229.

- ↑ Bruce, George, Harbottle's Dictionary of Battles, (Van Nostrand Reinhold Co.:New York, 1981),134.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Sedlar, Jean W.. East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000-1500. University of Washington Press. pp. 244. "Nearly the entire Christian fighting force (between 12,000 and 20,000 men) had been present at Kosovo, while the Ottomans (with 27,000 to 30,000 on the battlefield) retained numerous reserves in Anatolia."

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Cox, John K.. The History of Serbia. Greenwood Press. pp. 30. "The Ottoman army probably numbered between 30,000 and 40,000. They faced something like 15,000 to 25,000 Eastern Orthodox soldiers."

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Cowley, Robert; Geoffrey Parker. The Reader's Companion to Military History. Houghton Mifflin Books. pp. 249. "On June 28, 1389, an Ottoman army of between thirty thousand and forty thousand under the command of Sultan Murad I defeated an army of Balkan allies numbering twenty-five thousand to thirty thousand under the command of Prince Lazar of Serbia at Kosovo Polje (Blackbird's Field) in the central Balkans."

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "Kosovska bitka" (in Serbo-Croatian). Vojna Enciklopedija. Belgrade: Vojnoizdavacki zavod. 1972. pp. 659–660.

- ↑ Some sources attempt to give the date as June 28 in the New-Style Gregorian calendar, but that was not adopted for another two centuries. If it had been, the New-Style date in 1389 would have been only June 23.

- ↑ John VA Fine , The late mediaeval Balkans, p.409

- ↑ K.J. Jirecek,Illyrisch-Albanische forschungen, Munchen 1916,p.78

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 "Kosovska bitka" (in Serbo-Croatian). Vojna Enciklopedija. Belgrade: Vojnoizdavacki zavod. 1972. pp. 659.

- ↑ Duijzings, G., Religion and the Politics of Identity in Kosovo (London: Hurst, 2000)

- ↑ Hans-Henning Kortüm, Transcultural Wars from the Middle Ages to the 21st Century, Akademie Verlag, 231. "But having been established under Murad I (1362-1389), essentially as a bodyguard, the Janissaries cannot have been present in large numbers at Nicopolis (there were no more than 2,000 at Kosovo in 1389)."

- ↑ Hunyadi and Laszlovszky, Zsolt and József (2001). The Crusades and the military orders: expanding the frontiers of medieval latin christianity. Budapest: Central European University Press. Dept. of Medieval Studies. pp. 285–290. ISBN 963-9241-42-3.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 "Kosovska bitka" (in Serbo-Croatian). Vojna Enciklopedija. Belgrade: Vojnoizdavacki zavod. 1972. p. 660.

- ↑ Military history of Hungary (Magyarország hadtörténete), Ed.: Ervin Liptai, Zrínyi Military Publisher, 1985 Budapest ISBN 963-05-0929-6

- ↑ The Desperate Act: The Assassination of Franz Ferdinand at Sarajevo By Roberta Strauss Feuerlicht, pg. 22

- ↑ Wayne S. Vucinich & Thomas A. Emmert, Kosovo: Legacy of a Medieval Battle, University of Minnesota. 1991.

- ↑ Battle of Kosovo, Encyclopedia Britannica

- ↑ Kosovo Field, Columbia Encyclopedia

- ↑ "Battle of Kosovo", Encarta Encyclopedia. (Archived 2009-10-31).

- ↑ Historical Dictionary Of Kosova By Robert Elsie, pg.95

- ↑ The Encyclopedia of World History: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern, Chronologically Arranged By Peter N. Stearns, William Leonard Langer, pg. 125

- ↑ Global Terrorism By James M Lutz, Brenda J Lutz, pg. 103

- ↑ Parliaments and Politics During the Cromwellian Protectorate By David L. Smith, Patrick Little, pg. 124

- ↑ Genocide: a critical bibliographic review By Israel W. Charny, Alan L. Berger, pg. 56

- ↑ Bloodlines: From Ethnic Pride to Ethnic Terrorism By Vamik D. Volkan, pg. 61

- ↑ The Ottoman Empire, 1700-1922 By Donald Quataert, pg. 26

- ↑ History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey By Stanford Jay Shaw, Ezel Kural Shaw, pg. 24

- ↑ Slobodan Milošević: speech at Kosovo Polje, 28 June 1989, http://emperors-clothes.com/milo/milosaid2.htm (accessed 22 January 2007).

External links

- The Battle of Kosovo: Early Reports of Victory and Defeat by Thomas Emmert

- The Battle of Kosovo Serbian Epic Poems edited by Charles Simic

- The Legend of Kosovo

- Battle of Kosovo animated battle map by Jonathan Webb

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||